Upside-Down Markets: Profits, Inflation and Equity Valuation in Fiscal Policy Regimes

By Jesse Livermore+September 2020

Listen to Jesse Livermore* discuss this paper and market with Patrick O’Shaughnessy on the “Invest Like the Best” podcast

Listen to Jesse Livermore* discuss this paper and market with Patrick O’Shaughnessy on the “Invest Like the Best” podcast

An upside-down market is a market in which good news functions as bad news and bad news functions as good news. The force that turns markets upside-down is policy. News, good or bad, triggers a countervailing policy response with effects that outweigh the original implications of the news itself.

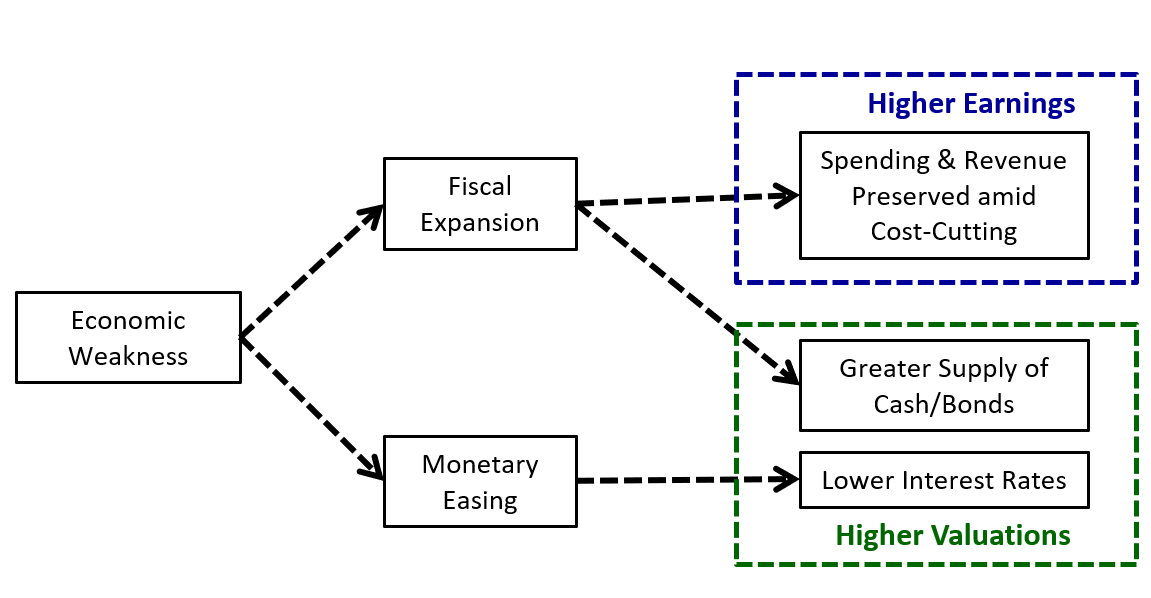

Most investors are familiar with upside-down markets as they exist in the context of monetary policy. Bad news can function as good news in a monetary policy context because it can cause central banks to lower interest rates. If the boost from lower interest rates outweighs the negative implications of the news itself, then the overall effect on the market can be positive.

Unfortunately, monetary policy is limited in what it can accomplish as a form of stimulus. It therefore offers a weak foundation for upside-down markets. We can celebrate economic problems as catalysts for interest rate cuts, but the cuts won't usually avert the problems, at least not in full. They may buoy stock prices through portfolio preference channels, but the damage to fundamentals will tend to outweigh the buoyancy.

Fiscal policy is an entirely different matter. If deployed in sufficient quantities, it can achieve any nominal level of spending or income that it wants. When policymakers commit to using it alongside monetary policy to achieve desired economic outcomes, markets have solid reasons to turn upside-down.

To illustrate with a concrete example, imagine a policy regime in which U.S. congressional lawmakers, acting with the support of the Federal Reserve ("Fed"), set a 5% nominal growth target for the U.S. economy. They pledge to do "whatever it takes" from a fiscal perspective to reach that target, including driving up the inflation rate, if the economy's real growth rate fails to keep up. Suppose that under this policy regime, the economy gets hit with a contagious, lethal, incurable virus that forces everyone to aggressively socially distance, not just for several months, but forever. The emergence of such a virus would obviously be terrible news for humanity. But would it be terrible news for stock prices?

The virus would force the economy to undertake a permanent reorganization away from activities that involve close human contact and towards activities that are compatible with social distancing. Economically, the reorganization would be excruciating, bringing about enormous levels of unemployment and bankruptcy. But remember that Congress is in-play. To reach its promised 5% nominal growth target, it would inject massive amounts of fiscal stimulus into the economy—whatever amount is needed to ensure that this year's spending exceeds last year's spending by the targeted 5%. To support the effort, the Fed would cut interest rates to zero, or maybe even below zero, provoking a buying frenzy among investors seeking to escape the guaranteed losses of cash positions.

The interest rate cuts, possibly into negative territory, would make stocks more attractive relative to cash and bonds. Additionally, the massive issuance of new government securities to fund the spending would shrink the relative supply of equity in the system, making stocks more scarce as growth-linked assets. Finally, the virus would give corporations financial cover to cut unnecessary labor expenses, allowing them to capitalize on any untapped sources of productivity that might be embedded in their operations. This action, which takes income away from households, would normally come back to hurt the corporate sector in the form of declining demand and declining revenue. But if the government is using fiscal policy to achieve a nominal growth target, then there won't be any income or revenue declines in aggregate. The government will inject whatever amount of fiscal stimulus it needs to inject in order to keep aggregate incomes and revenues growing on target, accepting inflation as a substitute for real growth where necessary.1

If you are a diversified equity investor in this scenario, you will end up with a windfall on all fronts. Your equity holdings will be more attractive from a relative yield perspective, more scarce from a supply perspective, and more profitable from an earnings perspective. The bad news won't just be good news, it will be fantastic news, as twisted as that might sound.

It may seem strange to think that stocks could benefit from bad news, but other asset classes that offer insured income streams, such as government bonds, behave that way. If the government is effectively insuring the income streams of the aggregate corporate sector, why shouldn't a diversified portfolio of stocks behave in the same way?

To be clear, the upside-down situation that I've described here is not the situation that we're currently in. From a policy perspective, legislators and central bankers have not implemented a nominal growth targeting regime, and the policy hawks that would normally serve as obstacles to such a regime have not yet been run out of town. But people on both sides of the aisle are increasingly coming to realize that fiscal policy is the "cheat code" of economics. If you're willing to tolerate inflation risk, you can use it to achieve any nominal outcome that you want. As people become more aware of this fact, they're going to increasingly challenge traditional approaches, demanding that fiscal policy be used to safeguard expansions and eliminate downturns. Upside-down markets will then become the norm.

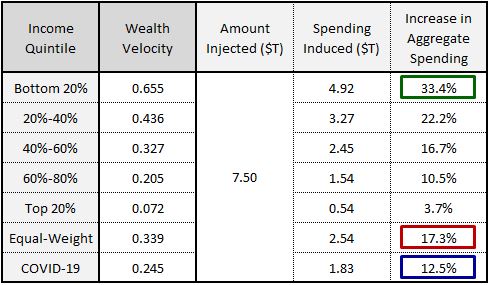

In this piece, I'm going to explore the dynamics of upside-down markets, focusing specifically on the current market, which is on the verge of being turned upside-down by the unexpectedly strong fiscal response to the COVID-19 pandemic. I'm going to analyze the effects that this response—roughly $7.5T (35% of GNP) in projected deficit spending over the next two years2—will have on three variables of interest to investors: (1) Corporate Profits, (2) Inflation and (3) Equity Market Valuation.

Each variable will be treated in its own section. Topics covered will include:

(1) Corporate Profits: A derivation of a modified version of the Kalecki-Levy profit equation, a graphing of each of the equation's terms over the course of U.S. economic history, a tentative forecast of the likely trajectory of corporate profits in the current environment using past trends in those terms as a guide, and a description of the paradoxical path through which future bad news could cause profits to rise.

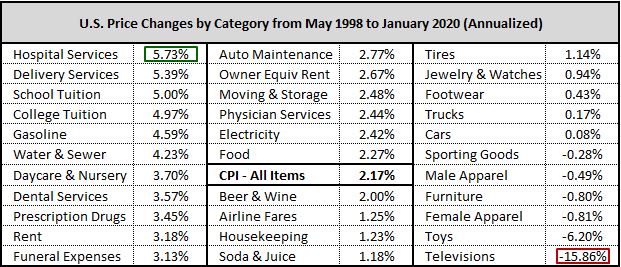

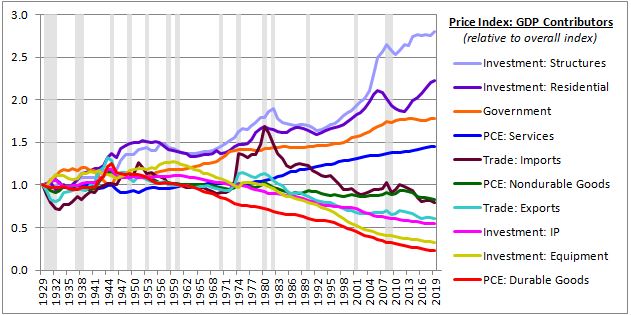

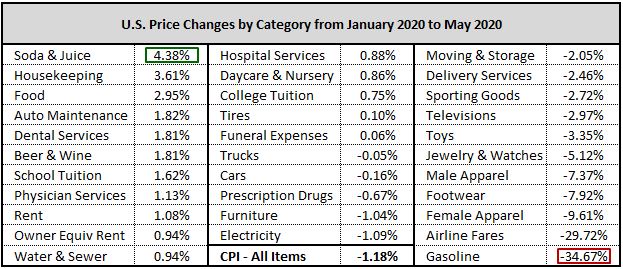

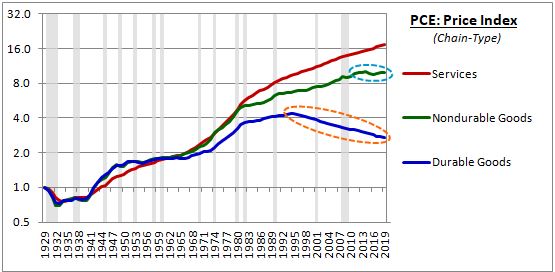

(2) Inflation: A description of the causes of inflation, a discussion of the ways in which expansionary fiscal policy can induce inflation and turn markets upside-down, and a quantitative estimate of the potential inflationary impacts of the government's monetary and fiscal responses to COVID-19.

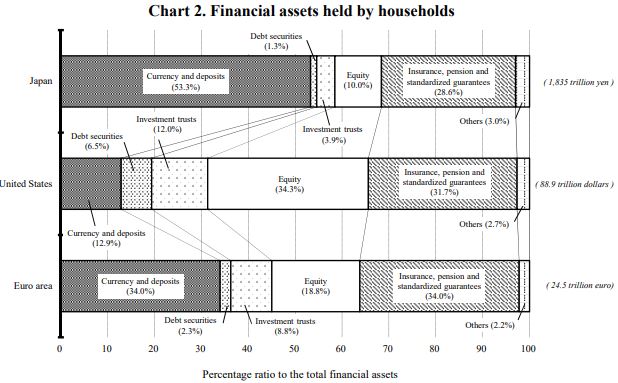

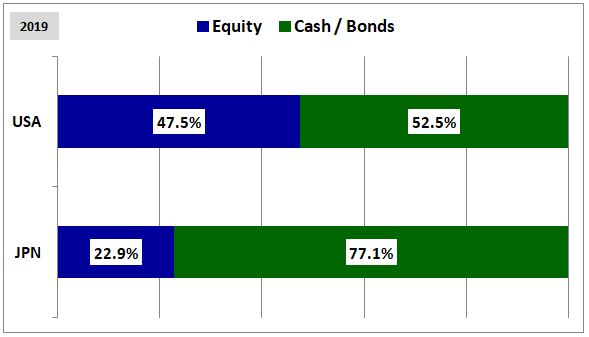

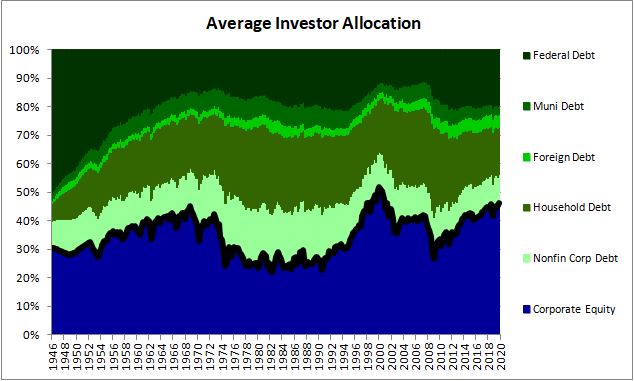

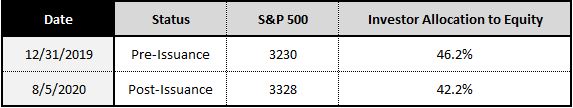

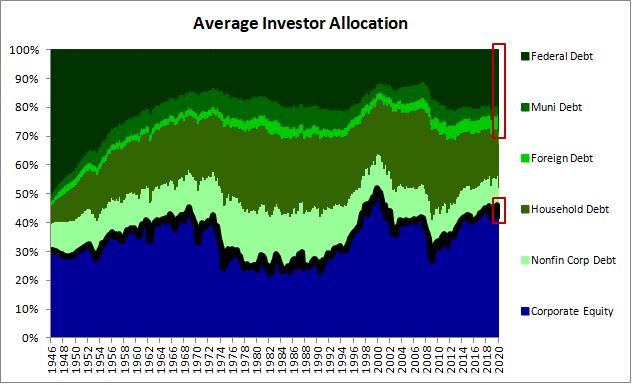

(3) Equity Market Valuation: A description of the financial market impacts of fiscal policy, a discussion of the relevance of attempted buying and selling flow and the like-for-like rule, an overview of the current state of asset supply in the United States, Europe and Japan, a discussion of the upside-down portfolio effects of the COVID-19 deficits, to include an estimate of the price level and valuation that the S&P 500 would have to rise to in order to restore average equity allocations to pre-pandemic levels.

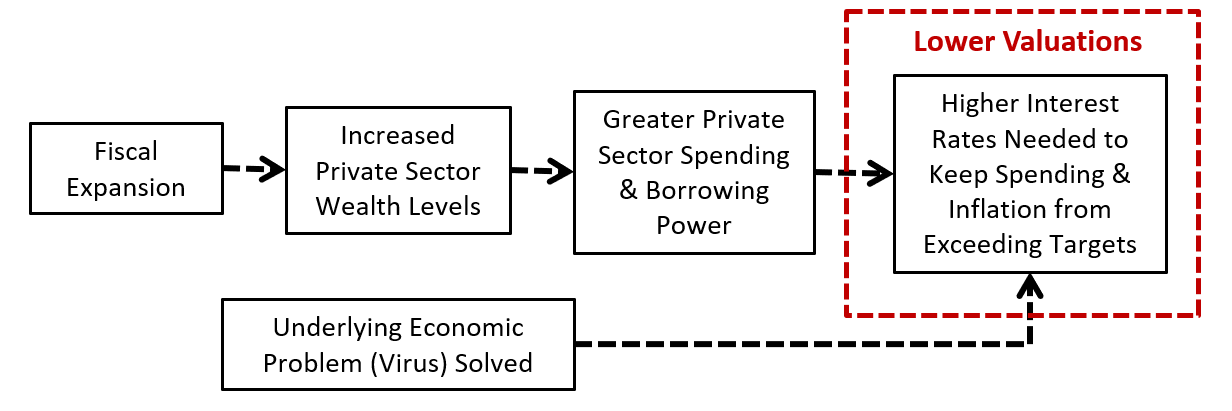

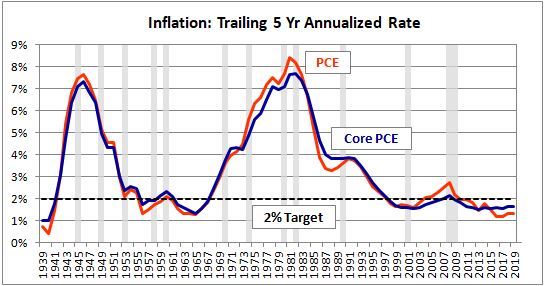

Right now, there's a bullish asymmetry in the potential for an upside-down dynamic to take hold. If things get worse, the economy will probably get more fiscal stimulus—potentially an unlimited amount, pending the outcome of the upcoming election. But if things get better, the Fed is not going to immediately tighten. Instead, the Fed is going to wait until it sees persistent demand-driven inflation above 2%—an outcome that could be difficult to achieve, particularly if inflation is measured on a core PCE basis. Of course, the investment community has already sniffed out this bullish asymmetry; it's one of the main reasons why the market has been able to set aside the ongoing uncertainties of the COVID-19 pandemic and trade its way back to all-time highs.

But the bullish asymmetry won't last forever. If we push hard enough on the fiscal side, we will eventually see inflation assert itself as a problem, causing a shift in the Fed's biases that brings the downside potential of an upside-down dynamic back into play. With markets trading near record valuations, the potential losses associated with such a dynamic could end up being quite significant.

Before moving on to the piece itself, I want to confess that it's very long—more than 40,000 words. I've tried not to waste space in it, but its length has nonetheless grown, mostly out of efforts to make its content as clear and precise as possible, and also because I've continued to push out its boundaries, using it as an excuse to lay out ideas and techniques that I find interesting. At this point, the piece is actually several stand-alone pieces merged together. If you're short on time, please feel free to skim the sections for charts and tables, using the links above to navigate to areas that you find interesting.

Fiscal stimulus works through the power of government deficits. The government puts more income into the economy through spending than it takes out through taxation, causing aggregate income to rise. Corporate profit is a form of income and therefore tends to increase through this process.

The precise analytic relationship between government deficits and corporate profits is captured in the Kalecki-Levy profit equation, an accounting identity originally articulated by the economist Jerome Levy in 1908. A modified version of the equation is shown below:

(1) Corporate Profit = Corporate Investment + Dividends + Current Account Balance + Government Deficit Spending + Household Deficit Spending

Without context, the equation can be difficult to intuitively grasp, so I'm going to build it out from a set of definitions and principles. I'm then going to graph its individual terms over the course of U.S. economic history, using profit trends observed in past fiscal expansions to estimate the likely trajectory of profits in the current fiscal expansion. Finally, I'm going to use the equation to explain the paradoxical impact that bad news can have on profits in an upside-down market.

Deriving The Kalecki-Levy Profit Equation

We can think of an economy as a collection of entities that exchange goods and services with each other. The exchanges are tracked through the earning and spending of money. When you deliver desired goods and services to others, money gets paid to you. When others deliver desired goods and services to you, you give the money back. Crucially, the spending of each entity in the system gives rise to the income of other entities, which, when spent, gives rise to the income of yet other entities, and so on in complex interconnected cycles of exchange.

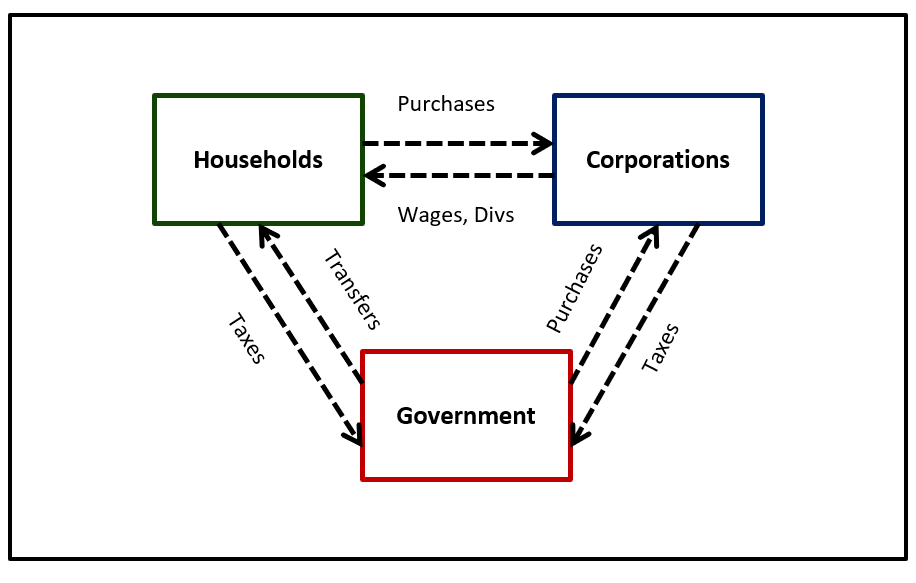

To simplify, we can separate the entities in this process into three core sectors: households, corporations, and the government. As aggregate entities, these sectors interact with each other in the way described above. Each sector receives income from other sectors in exchange for the value that it adds, and each sector spends that income back into other sectors to get that value back. The chart below illustrates the flows:

The fact that the income of each entity in the system arises out of the spending of other entities introduces a potential problem. As self-interested entities, households have a natural desire to "save", i.e., increase their "wealth" over time, which includes the real property that they own and the financial claims that they've accumulated on the system.3 The easiest way for them to save is for them to withhold some of their income from the process, i.e., not spend it back into the system after they receive it. When they withhold their income in this way, their accumulated claims on the system increase and they become wealthier. The problem, however, is that other entities in the system, including other households, lose the income that the withheld spending would have otherwise turned into. Unless those entities are willing to borrow, sell assets, or drawdown on previously withheld income, they will have to reduce their own spending, which will reduce the income of other participants down the line, and so on in a vicious cycle.

To sustain the flow of income through the system, households need to save their income in a way that also entails spending that income. Intuitively, it may not seem possible to save income and spend it at the same time, but that's only because we wrongly equate spending with consumption. When people spend their income on consumption, they use up what they've spent, so if they want to grow their wealth over time, they have to set aside a portion of their income and not spend it in that way. But there's another way they can spend it: by investing it. Investment is a type of spending that is also a type of saving; it solves the problem.

As used here, the term investment has a very specific meaning. It means the creation of a new asset, something with lasting economic value. When people earn income and invest it, their wealth grows because they gain the new asset. In funding the creation of that asset, they spend the income that they're seeking to save, transferring it to other entities in the economy. In this way, they're able to grow their accumulated wealth while also supporting the income and wealth of others.

For an illustration, consider the most common household investment—a home. When a household sets aside a portion of its income and uses the income to fund the construction or improvement of a home, its wealth grows because it converts a portion of its income into something with lasting economic value, as opposed to something that gets quickly used up. The incomes of other entities in the system are maintained during the process because the household spends the underlying money in the process of saving it. The household pays the money to the architects that design the home, the laborers that build it, and so on, creating income for those other entities.

To be clear, the term investment, as we're using it here, does not mean buying an existing asset from someone else—e.g., an existing share of stock in a company, an existing home, an existing factory, etc. When you do that, all that you're doing is swapping places with someone else in the system—that person is taking your money, and you're taking that person's shares (or their home, or their factory). Unless that person saves the money in a way that creates income for others, it will be taken out of the system with the same effect as if you had taken it out yourself.

To formalize these distinctions, we can list three things that a person can do with his or her income:

(a) Consume (spend without saving): A person can consume the income, spending it in a way that does not leave behind any value. Consumption is a way of spending without saving.

(b) Invest (spend and save at the same time): A person can invest the income, using it to fund the creation of a new asset. Investment is a way of spending while also saving. It represents a positive-sum game for the overall system. The investor gains by acquiring a new asset, and others gain by receiving the income that the investor spends in the process. The economy gains because it ends up with more assets, more wealth.

(c) Withhold (save without spending): A person can withhold the income, removing it from circulation. Withholding is a way of saving without spending. In contrast to investing, it represents a zero-sum game for the overall system. Any increase that you experience in your wealth by withholding your income will necessarily come at the expense of the person to whom your income would have otherwise gone, had it been spent.

To withhold is to receive more income than you spend, and therefore the opposite of withholding is to spend more income than you receive, i.e., to Deficit Spend. Deficit spending can be for consumption, which will lead to a reduction in current wealth, or for investment, which will leave current wealth unchanged (given that you will gain an asset in exchange for the deficit you incur). Deficit spending can be funded with money previously withheld, money obtained through the sale of current wealth, money obtained by borrowing against current wealth, or, in the case of the government, newly created or "printed" money.

Returning to the Kalecki-Levy profit equation, the starting point for the equation is the simple insight that there are two ways to save—by investing and by withholding. The total quantity saved is the sum of the two:

(2) Saving = Investment + Withholding

As explained above, withholding is a zero-sum game--one person can only do it if someone does the opposite of it. For the aggregate economy, total withholding must therefore be zero:

(3) Withholding = 0

For the aggregate economy, it follows that saving equals investment:

(4) Saving = Investment + Withholding (0)

We refer to (4) as the saving-investment identity. This identity reflects the insight that the only way that an economy, in aggregate, can "save", i.e., grow its wealth over time, is by investing its income, i.e., using that income to fund the creation of new wealth. If an economy attempts to save by investing its income, the investment will increase overall wealth in the system while preserving the flow of income through the system. But if an economy attempts to save by withholding its income, it will run into a dead-end. No new wealth will be created, and each person's attempt to withhold income will occur at the direct expense of the income of others who are attempting to do the same thing.

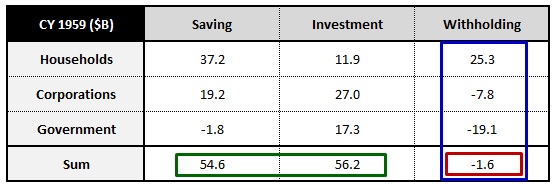

To illustrate this point in data, consider the table below, which shows the actual saving, investment and withholding behaviors of the U.S. household, corporate and government sectors for calendar year 1959.4 The data are taken from the National Income and Products Account (NIPA) published by the Bureau of Economic Analysis (BEA):

To understand the terms in the table, imagine that each sector starts the year with a certain amount of wealth. Its participants then engage in cycles of income generation and spending that track the production, exchange, and consumption of goods and services. The "saving" of each sector, shown in the second column, is simply the increase in wealth that the sector experiences over the course of the year.5 The "investment" of each sector, shown in the third column, is the amount of money that the sector deploys into the creation of new assets during the year, net of depreciation. The "withholding" of each sector, shown in the fourth column, is the amount of income that the sector fails to spend during the year.

For the year 1959, households saved $37.2B. Of that saving, $11.9B occurred in the form of investment and $25.3B occurred in the form of withholding. Withholding is a zero-sum game, so the fact that households successfully withheld $25.3B means that corporations and the government, as a group, must have negatively withheld—i.e., deficit spent—that same amount. In examining the table, we see that this is exactly what they did. As indicated in the blue box, corporations withheld negative $7.8B and the government withheld negative $19.1B. The sum comes out to negative $26.9B, a near perfect offset to the household sector's $25.3B of positive withholding. The total withholding for the overall economy, captured in the red box, was roughly zero, consistent with (3) above.

The data also confirms the saving-investment identity expressed in (4). As indicated in the green box, the aggregate saving of $54.6B is roughly the same as the aggregate investment of $56.2B. BEA data collection is not perfect, but if it had been, and if there had been no other contributors to the process, then the numbers would have been exactly the same.

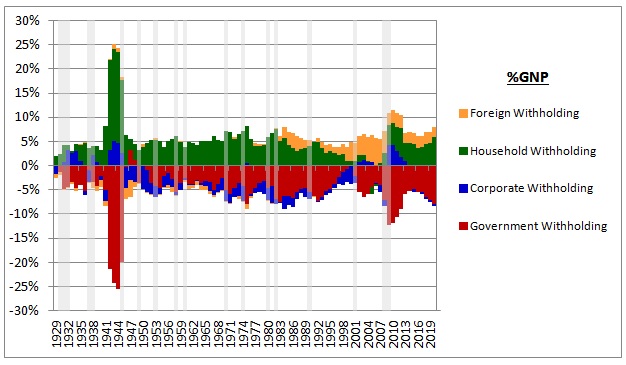

In the above analysis, we ignored the impact of the foreign sector. The foreign sector can withhold against a nation's economy by receiving more income from the international trade process than it sends back through that process. Total withholding including the foreign sector must be zero, so if the foreign sector positively withholds, then the economy will have to negatively withhold, i.e., deficit spend, to make up the difference. This constraint is reflected in the chart below, which shows the annual historical withholding of the household, corporate and government sectors of the U.S. economy alongside the withholding of the foreign sector from 1929 through 2019:

As you can see, the sum total of the withholding from all of the sectors is almost exactly zero in every year. In the case of the U.S., the government and the corporate sector tend to negatively withhold, i.e., deficit spend. Their deficit spending injects money and debt securities—financial wealth—into the household and foreign sectors, which those sectors positively withhold.

In examining the chart, it's important to recognize that withholding is not always a choice. In situations where deficit spending is occurring, it's a forced outcome. When a given sector or entity engages in deficit spending, whether through borrowing, money printing or the drawing down of past income withholdings, it injects financial wealth into the rest of the system. Someone in the rest of the system has to hold—i.e., "withhold"—that wealth at all times.

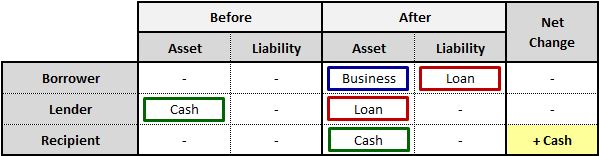

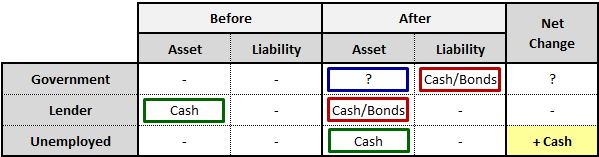

To illustrate with an example, when the government engages in deficit spending through traditional borrowing, two private sector entities are affected: (1) the person that lends to the government and (2) the person that receives the associated government spending as income. The lender trades cash for a bond of equal value and is left with an unchanged wealth position. The spending recipient, in contrast, ends up with income, new wealth to his or her name. That person might spend the income, creating income for another person, who might spend it, creating income for yet another person, who might spend it, and so on. Each person can decline to withhold the income, choosing to spend it into the coffers of someone else, but if we stop the clock on the process at a given time to collect data, we're going to find that someone is holding it at that time, having yet to spend it. That person will show up as having "withheld" it—not necessarily by choice, but by necessity, given that deficit spending took place.6

The rules governing deficit spending and withholding, then, are as follows:

Injection: Deficit spending on the part of a given entity injects financial wealth into the rest of the system.

Removal: Withholding on the part of a given entity removes financial wealth from the rest of the system.

Logically, whatever is injected by one entity has to be removed (i.e., received) by another. Whatever is removed by one entity has to be injected (i.e., provided) by another. In that sense, deficit spending forces withholding to occur, and withholding forces deficit spending to occur. Neither can occur without the other occurring.

Economically, the question that matters is: when a given entity injects financial wealth into the rest of the system through deficit spending, how much additional spending does the injection generate in the process of being withheld? Again, the wealth has to be withheld, but the process through which it gets withheld can entail significant chains of spending from person to person, entity to entity. We refer to these chains as instances of multiplication—a.k.a., "the Keynesian multiplier effect."

The same question can be posed in reverse: when a given entity removes financial wealth from the rest of the system through withholding, how much existing spending will be destroyed before someone finally deficit-spends to make up the difference? Again, someone will have to deficit-spend, but the process through which the deficit spending gets elicited could entail significant reductions in spending by people who do not want to deficit-spend. You might decide not to spend your income, taking income away from others and forcing them to either deficit-spend or cut back on their own spending. If they choose to cut back on their own spending, then they will have done what you just did, propagating the same outcome further down the system. A single reduction in spending will have then destroyed multiple instances of existing spending. We refer to this destruction as negative multiplication. It represents the opposite of the Keynesian multiplier effect.

Returning to the saving-investment identity, we can center the identity on the domestic economy by subtracting out the saving that an economy accomplishes by running a trade surplus on the foreign sector. This saving is captured in the current account balance. Adjusting (4), we get:

(5) Saving - Current Account Balance = Domestic Investment

What (5) is saying is that any aggregate saving that an economy's households, corporations and government engage in that is not accomplished by running a surplus on the rest of the world must be accomplished through domestic investment.7

Now, the saving term is just the saving of the household sector plus the saving of the corporate sector plus the saving of the government sector. We can therefore rewrite (6) as:

(6) (Household Saving + Corporate Saving + Government Saving) - Current Account Balance = Domestic Investment

Corporate saving is simply retained earnings, i.e., corporate profit (after taxes) minus the dividends that corporations pay out. Substituting, we get:

(7) Household Saving + (Corporate Profit - Dividends) + Government Saving - Current Account Balance = Domestic Investment

Rearranging the terms so that corporate profit is on the left side, with everything else on the right side, we arrive at the Kalecki-Levy equation in its traditional form:

(8) Corporate Profit = Domestic Investment + Dividends + Current Account Balance - Household Saving - Government Saving

We can make the equation more useful and intuitive by taking it a few steps further. The investment term is the sum of household investment (e.g., building new homes), corporate investment (e.g., building new factories), and government investment (e.g., building new warships).8 We can therefore rewrite the equation as:

(9) Corporate Profit = (Household Investment + Corporate Investment + Government Investment) + Dividends + Current Account Balance - Household Saving - Government Saving

Now, the saving of each individual sector is simply the sum of what it saves by investing and what it saves by withholding:

(10) Saving = Investing + Withholding (for an individual sector)

Substituting (10) into (9) for households and the government, we get:

(11) Corporate Profit = Household Investment + Corporate Investment + Government Investment + Dividends + Current Account Balance - (Household Investment + Household Withholding) - (Government Investment + Government Withholding).

The household investment term shows up as a positive and a negative--it therefore cancels out. The government investment term cancels out in the same way.

(12) Corporate Profit = Household Investment + Corporate Investment + Government Investment + Dividends + Current Account Balance - (Household Investment + Household Withholding) - (Government Investment + Government Withholding).

We end up with:

(13) Corporate Profit = Corporate Investment + Dividends + Current Account Balance - Household Withholding - Government Withholding

Now, in the case of the government, the withholding is normally negative, meaning that the government normally spends more money than it receives through taxation. To fund the difference, it either borrows money or prints money—from a fiscal perspective, these actions are effectively the same. We can therefore rewrite the negative government withholding term as a positive government deficit spending term. We can make the same change for households, replacing their negative withholding term with a positive deficit spending term. We end up with the modified version of the equation presented at the outset of the piece:

(14) Corporate Profit = Corporate Investment + Dividends + Current Account Balance + Government Deficit Spending + Household Deficit Spending

This modification offers two benefits over the original version. First, it transforms the terms so that they are all positive. It therefore allows us to represent the end result, corporate profits, as a stacked sum of quantities on a graph. Second, the modification simplifies the investment term down to the investment of one sector—the corporate sector. When analyzing corporate profits, the investment of the corporate sector is the only type of investment that we need to pay attention to. Corporate profits don't care how households and the government spend money—i.e., whether they spend it on investment or on consumption. As long as the money gets spent, the profit that corporations receive ends up being the same. The modified equation reflects this fact.

It's important to clarify that the equation is not a causal theory. It doesn't tell us anything about the microeconomic drivers of corporate profitability—e.g., supply, demand, competition, pricing power, etc. Instead, it's a macroeconomic accounting identity that holds true by definition. We can think of it as telling us that (1) financial wealth that gets injected through deficit spending ends up landing somewhere, on someone's balance sheet and (2) financial wealth that gets removed through withholding ends up being taken from somewhere, from someone's balance sheet. The equation tracks where financial wealth ends up landing and where it ends up being taken from, focusing specifically on the outcome for the corporate sector.

For those with lingering questions as to how the equation works, I've written up an intuitive description of the dynamics of each term below. Feel free to skip past the description if the dynamics are already sufficiently clear to you:

(a) Corporate Investment: One corporation's investment represents spending that becomes the revenue, and therefore the profit, of another corporation. On a net basis, this spending is not treated as a cost to the original corporation, and therefore it does not subtract from the original corporation's profit. But it adds to the profit of the receiving corporation. Aggregate profit for the overall corporate sector therefore rises as a consequence of the investment.

Now, in addition to profit, a portion of corporate investment spending will become wages and taxes for households and the government, respectively. But if these sectors are maintaining a constant withholding (i.e., if we are keeping their terms in the equation unchanged), then the implication is that they are spending the associated money back into the corporate sector. It follows that, with the other terms in the equation held constant, overall corporate profit will increase by the exact amount of any increase in corporate investment.

(b) Dividends: Dividends represent income paid by corporations to the households that own them. Importantly, these payments are not costs to the corporation. They're simply changes in the ways in which the owners of the corporations hold the underlying wealth. Before payment, the owners hold the wealth as money inside the companies; after payment, they hold it as money in their own accounts.9

If households keep their withholding constant while the corporate sector increases the dividends that it pays to them, the implication is that households are spending that dividend back into the corporate sector, either on consumption or on investment. The same is true for taxes that get extracted in the process—if the government keeps its withholding constant amid the increased income that it receives from taxes on the dividends, the implication is that the government is spending those taxes back into the corporate sector. In either case, if the other terms in the equation are held constant, any increase in the dividends that the corporate sector pays will end up back in the corporate sector as an increase in profit.

(c) Current Account Balance: Simplistically, we can say that the corporate sector earns more when it sells more abroad. A higher current account balance therefore implies higher corporate profits. More precisely and accurately, we can say that the current account balance represents a form of saving that has to show up somewhere, as a wealth gain for someone. If the other terms in the equation all remain constant as the current account balance rises, the implication is that the wealth gain is accruing to corporations, showing up as corporate profit.

(d) Government and Household Deficit Spending: If households or the government deficit spend into the corporate sector, the associated spending will show up as increased revenue and increased profit. Some of the revenue will go back to households in the form of wages and back to the government in the form of taxes, but again, assuming that the associated income is not withheld (which would change other terms in the equation), then it will be spent back into the corporate sector, where it will show up as profit. Similarly, if households and governments deficit spend into each other's coffers, and if they do not withhold the income injected by the spending, then the implication is that they are spending the income back into the corporate sector, where it will again show up as profit.

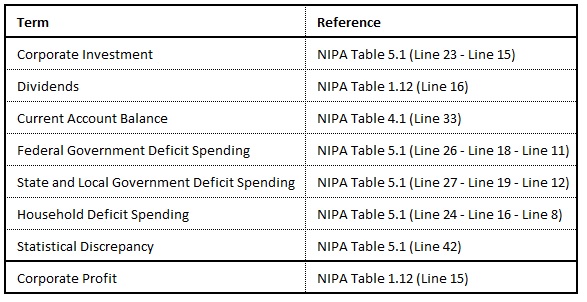

We can empirically verify the accuracy of the equation using historical NIPA data. The table below lists the specific NIPA tables and line items that quantify each term. Note that all terms are shown on a net basis—net of depreciation, taxes, and so on:

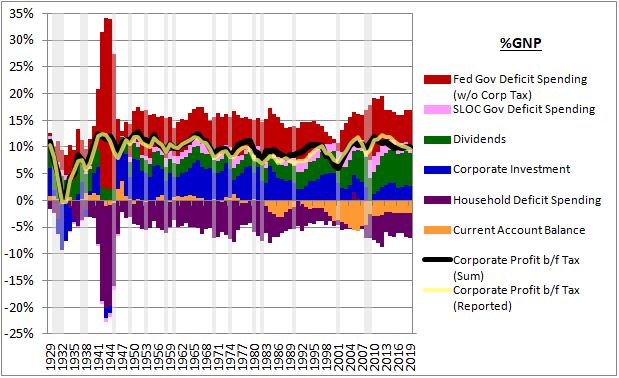

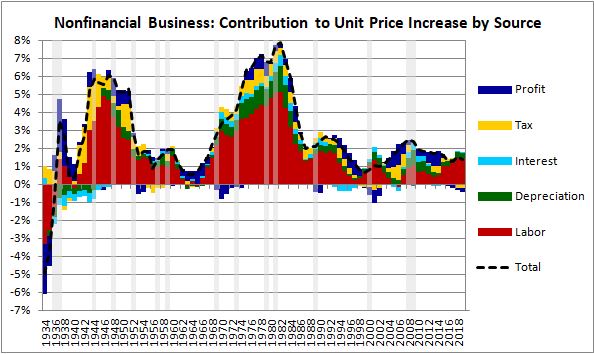

The chart below tracks the terms in the equation from 1929 through 2019, with each term expressed as a percentage of Gross National Product (NIPA Table 1.7.5, Line 4).10 If the equation is correct, then corporate profit should equal the sum of each term:

The sum of the terms is shown as the black line and the actual reported corporate profit, published by NIPA, is shown as the yellow line (both as percentages of GNP). As you can see, the two lines track each other very closely, about as closely as one can reasonably expect for a real-world data collection process that covers such a large scale. The BEA publishes a statistical discrepancy term that captures measurement error in the data collection process. If that term is subtracted from the black line, the match with the yellow line becomes exact.

Notice that the household deficit spending term, shown in purple, is almost always negative. The negative sign indicates that households positively withhold a portion of their income each year. Households are significantly more inclined to positively withhold income than other sectors because they are the only sector that consists of actual people. As actual people, they have legitimate reasons for seeking to grow wealth—they benefit from the increased security, stability, optionality, and status that additional wealth brings. The other sectors—corporations and the government—are not actual people, but rather constructs that exist to serve people. Their withholding and deficit spending decisions are not based on self-interest, but on the specific interests of the households that own them and elect them.

Why do households save by withholding? Why don't they save by investing? Because opportunities for them to save by investing—for example, by starting new businesses—aren't always practical or attractive from a risk-reward standpoint. To deliver attractive returns, new investment has to be beneficial to the economy relative to its costs. But it isn't always beneficial, and it doesn't magically become beneficial simply because households want to save.11

Returning to the chart, notice that the government deficit spending term, shown in red, is almost always positive. It has to be positive to offset the consistent positive withholding that the aggregate household sector engages in. As emphasized earlier, withholding on the part of one entity in the system requires deficit spending on the part of another. In practice, the entity that deficit-spends to make household withholding possible is the government.

If households and corporations were to deficit spend in the way that the government deficit spends, they would eventually run up against liquidity and solvency constraints. But a sovereign government is not subject to those constraints. Through its central bank, it decides the interest rate at which it borrows. And it doesn't even need to borrow—it can finance spending by printing new money. As long as there are economic participants willing to withhold the new money, and as long as the economy has the productive capacity to fulfill any additional spending that the withholding process might give rise to, economic problems such as inflation need not emerge.

This insight, most notably attributable to the British economist Abba Lerner, is a core component of Modern Monetary Theory (MMT). As the insight becomes better understood in political circles, it will increasingly drive fiscal policies that seek to guarantee desired levels of income and spending growth in the economy, policies that have the potential to turn markets upside-down, for better or worse.

Corporate Profits: Data Across History

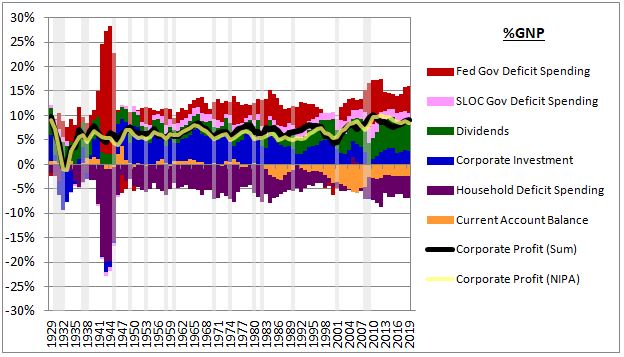

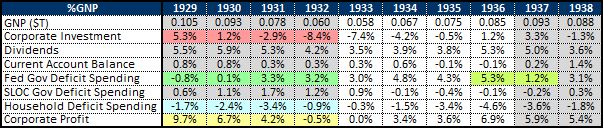

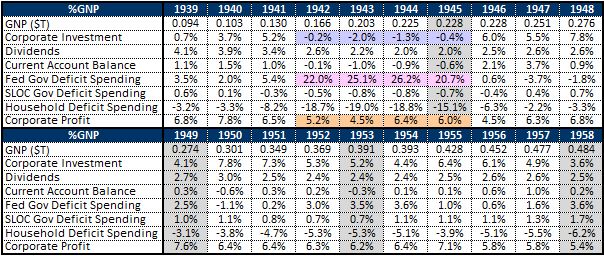

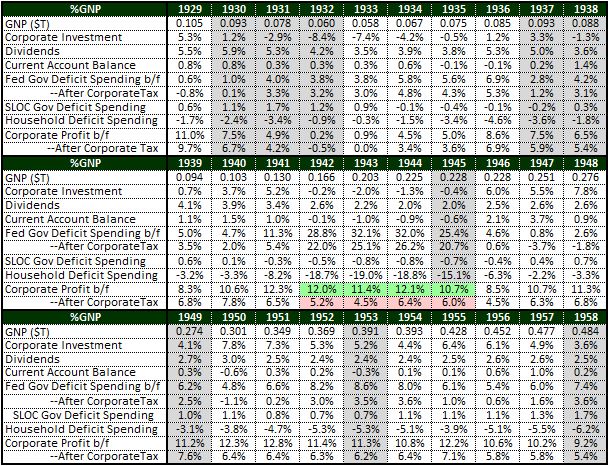

To estimate likely outcomes for corporate profits in the current environment, we can examine how the individual terms in the profit equation behaved in past environments. The table below shows each term as a percentage of GNP for each year from 1929 through 1938. Note that we separate government borrowing into Federal and State and Local (SLOC):

In the aftermath of the 1929 stock market crash, the U.S. economic outlook significantly deteriorated. Reduced employment and reduced income led to a substantial increase in the propensity to save, while reduced demand and reduced tolerance for risk led to a substantial decrease in the need for new investment and the willingness to undertake it. The extreme mismatch between the desire to save and the desire to invest led to a situation in which all parts of the economy attempted to withhold income at the same time. The attempted withholding caused employment and income to fall further, which caused the desire to save to become even stronger and the desire to invest to become even weaker, leading to even more attempted withholding, and so on in an imploding vacuum—the reverse of a multiplier effect.

The optimal relief valve for a destructive process of this type would be the federal government, which has the capacity to deficit spend in a way that quenches the extreme withholding demand and restores the flow of income through the system. Unfortunately, the federal government did not mount an aggressive fiscal response, and the economy continued to collapse on itself. By 1932, nominal GNP had fallen by more than 40%, unemployment was at record levels, and corporate investment and corporate profit had both fallen below zero.

Interestingly, despite the extreme amount of financial stress experienced during the period, household withholding did not appreciably rise. But that's only because it couldn't appreciably rise. Withholding is a zero-sum game, and other sectors in the economy, in particular the federal government, weren't engaging in sufficient deficit spending to make the game possible.

By the mid 1930's, the economy had returned to growth, supported by a much stronger fiscal response. However, in 1937, the introduction of new taxes, specifically the new social security payroll tax, led to a significant drop in government deficit spending. Private sector withholding demand did not fall by an amount sufficient to accommodate this drop, and the economy again entered recession. Government borrowing eventually increased to pull the economy out of recession, and by 1941, corporate investment and corporate profits were at decade highs.

During World War II, the government engaged in an enormous amount of deficit spending to build military equipment, conduct military research, fund military operations, and pay military salaries.12 This spending led to a significant increase in all incomes, including corporate profit:

Recall that government deficit spending injects wealth into the private sector that must be withheld. In the case of World War II, the wealth that the government injected was primarily withheld by the household sector, which raised its withholding from 3.3% of GNP in 1940 to a peak of 19% in 1943. The corporate sector withheld the remainder, around 5%.

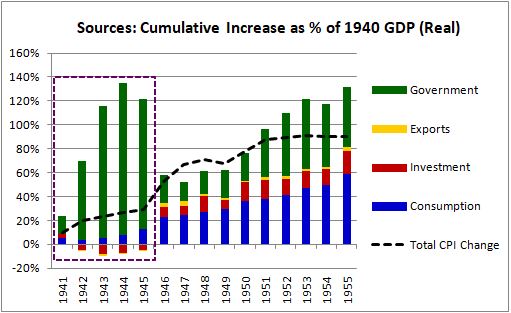

Interestingly, the government's injection was withheld by the private sector without stimulating appreciable amounts of spending, indicating a low multiplier effect. We can see this outcome in the boxed area of the chart below, which shows the cumulative change in the four sources of GDP as a percentage of 1940 GDP:

As you can see, government spending increased dramatically, but the increase did not translate into an appreciable increase in personal consumption spending or domestic investment spending. The injected wealth was quickly withheld, without jumping around in a large number of spending-turned-income-turned-spending cycles.

The lack of appreciable multiplication in response to the deficit spending was largely a forced outcome. The war production board forcibly shifted private capacity towards war production, creating domestic supply shortages. To address these shortages, goods, services, and credit were rationed. So, households didn't really have the option of spending the wealth that was being injected. They had to withhold it. Even if they had been allowed to spend it, they had good reasons not to. Those who were off fighting had little to spend it on, and those who remained at home needed to build up savings, given the uncertainty of who would return.

There's a loose analogy in this respect to the coronavirus pandemic, where government borrowing has significantly boosted aggregate household income relative to what it would have otherwise fallen to. As in World War II, the financial wealth injected through this boost is likely to be withheld by households without appreciably multiplying in spending, first because the fragile employment environment has dampened household confidence, and second because households have had to take measures to avoid contracting and spreading the virus. These measures have reduced or eliminated a substantial number of activities that households would have otherwise spent money on—group outings, vacations, sporting events, etc.

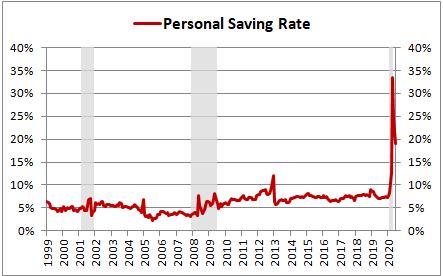

The increase in household withholding is already evident in the data. Using the personal saving rate as a proxy, we see a massive jump in April, the worst period of the lockdown, followed by a partial retreat to elevated levels in May and June (source: FRED): 13

This jump has been made possible by the large government deficit, which has injected new wealth that the private sector can withhold—indeed, that the private sector must withhold.

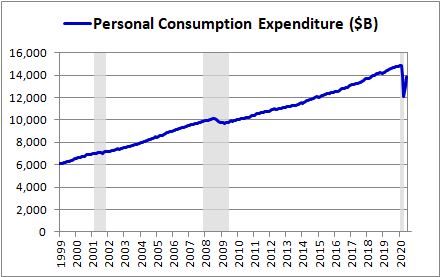

Unsurprisingly, the jump in withholding has coincided with a sharp drop in personal consumption expenditure (PCE), shown below on a seasonally-adjusted annualized basis (source: FRED):

The fact that PCE dropped by such a large amount despite the stimulus confirms the severity of the impairment that the pandemic has introduced into the multiplier. While the massive injection has surely increased spending relative to the counterfactual of no injection, the increase hasn't been enough to nominally offset the contractionary impact of the pandemic itself.

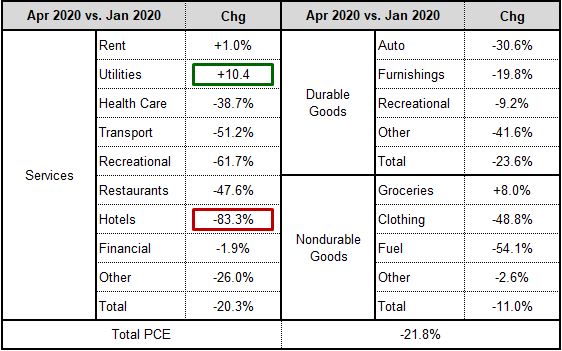

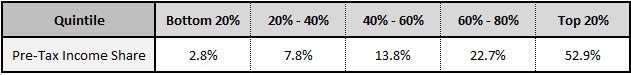

The table below shows the decline in PCE by category from the January peak through the April trough (source: NIPA Table 2.4.5U). Note that these numbers are derived from seasonally-adjusted annualized rates for the individual months rather than trailing rates for the prior year:

Unsurprisingly, spending on virus-impaired service industries, such as hotels, health care, recreation (e.g., gyms, live events), transportation (e.g., airlines), and restaurants suffered severe declines, while spending on goods associated with life under shelter-in-place orders, such as groceries, experienced countertrend expansions. The money to spend is there, thanks to the government's deficit spending. The problem is that it can only be spent in certain places.

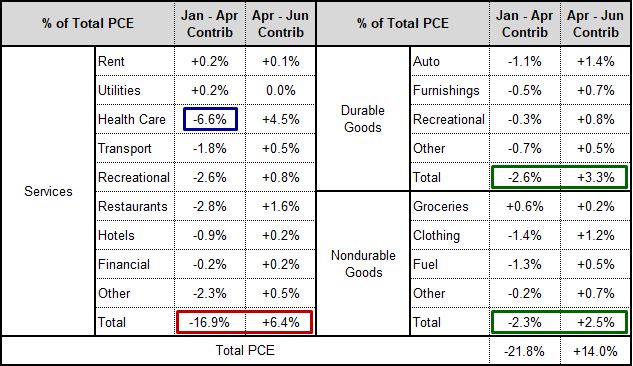

In May, many parts of the economy re-opened, freeing more of the injected wealth to be spent. For perspective on the nature of the recovery in different industries, the table below shows the January-to-April declines as a percentage of total January PCE alongside April-to-June increases as a percentage of total January PCE:

In comparing January to April, we see that the biggest negative contributor to the total PCE change was healthcare spending, which was responsible for -6.6% of the -21.8% change in total PCE. Healthcare spending is a large contributor to overall consumption spending, and it dropped significantly as patients actively avoided non-Covid-19 interactions with the medical system. During May and June, healthcare spending recovered by an amount equal to 4.5% of total January PCE, significantly less than the amount lost through April.

This incomplete recovery is mirrored across all services industries affected by the virus—recreation, restaurants, transportation, hotels, and so on. The obstacle to recovery in these industries is not demand—rather, it's the virus. The continued presence of the virus has continued to impair their ability to deliver services in ways that customers consider to be safe. No amount of stimulus is going to remove that obstacle. The threat of the virus itself has to be removed, through effective containment, convenient treatments that actually work, and ultimately, a vaccine.

Returning to the example of World War II played out, as the war played out, corporate investment fell from its pre-war levels, further offsetting the profit contribution of the government's borrowing. It fell because the economy's labor and capital resources had been forcibly redirected towards the war-fighting effort and were not available to be deployed into domestic business expansion. On a net basis, the only substantial investment that took place in the economy was government investment related to the war.

This outcome again provides a loose analogy to the coronavirus pandemic. Corporate investment is likely to drop, first as a consequence of increased corporate risk aversion related to the spike in uncertainty and the near-term shock to cash flows, and second, because many forms of investment are not practical, given virus-related concerns and constraints. We may see a redirection of corporate investment—for example, away from new commercial real estate construction towards technology supportive of remote work—but in terms of aggregate corporate investment, the sum of everything, we should expect to see a drop relative to pre-pandemic levels.

In an environment where the multiplier effect is weak, the private sector withholding that occurs in response to deficit spending will tend to preferentially occur at the location where the deficit spending is injected. The government puts income into that location through the spending and it simply stays there, without appreciably multiplying through the system. In the case of World War II, most of the spending was injected into the corporate sector, used to purchase military equipment that the defense industry was producing. On that basis, we would have expected to have seen a very large increase in corporate profit relative to other forms of income. When we look at the table, however, we see that such an increase did not actually occur. As a percentage of GNP, corporate profit peaked at roughly 5.6%, a low value by historical standards.

The primary cause of the lack of relative strength in profit during World War II was the federal government, which implemented a large excess profit tax to collect the windfall that the corporate sector was receiving. The result reflected an inversion of the principle described above: when the government takes wealth and income out of the private sector through taxation, the wealth and income losses that the private sector incurs tend to be preferentially incurred at the tax location, the place from which the wealth and income are taken. In the case of World War II, the wealth and income were preferentially taken from the corporate sector through the excess profit tax, just as they were preferentially injected into that sector through military spending. For overall profits as a share of national income, the result was largely a wash.

The excess profit tax represents a key disanalogy between World War II and the current environment. While it's conceivable that a future administration could attempt to raise the corporate tax rate to recoup some of the money currently being spent on stimulus and stabilization, the size of the tax increase is unlikely to be anywhere near the size of the wartime excess profits tax, which in some cases exceeded 90%.

To optimize the World War II analogy for this difference, we can reformulate the equation to track corporate profits on a pre-tax basis. We simply take federal corporate taxes paid and add it to both sides of the equation--to the corporate profit term on one end, reflecting what profits would have been without the excess profit tax, and to the federal government deficit spending term on the other, reflecting the additional money that the federal government would have had to borrow had the tax not been collected. We end up with the following chart:

The numbers are shown in the table below:

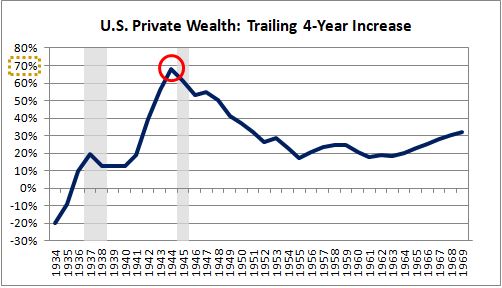

As you can see, the peak pre-tax profit during World War II was around 12% of GNP, more than twice the amount of the peak after-tax profit. This level of pre-tax profitability, which was 2% higher than the level seen in 2019, was among the highest levels observed in all of U.S. history.

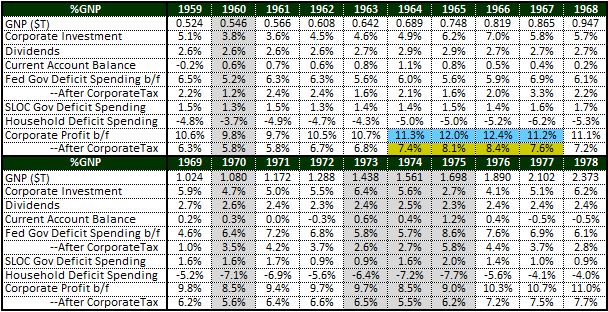

The table below shows the values of the equation from 1959 through 1978:

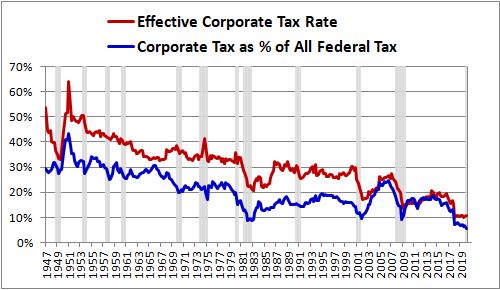

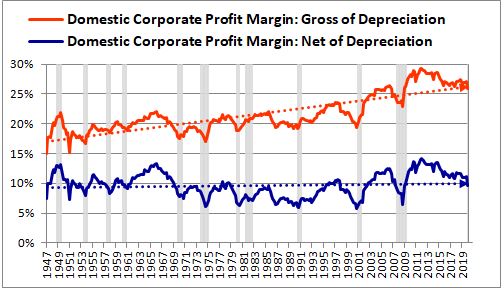

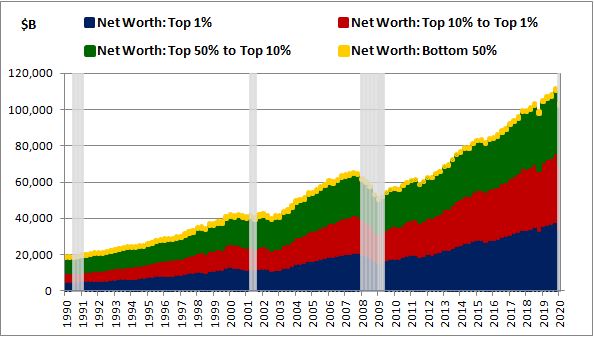

The elevated gap between pre-tax profits and after-tax profits seen during the period reflects the augmented role that corporate taxation came to play as a source of government revenue during and after the war. This role has since declined, coinciding with an increase in after-tax corporate profitability (source: FRED):

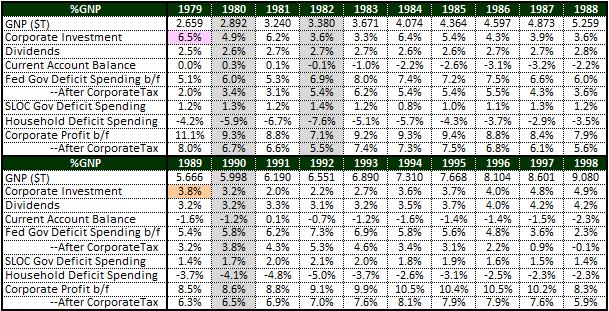

The table below shows the values of the equation from 1979 through 1998:

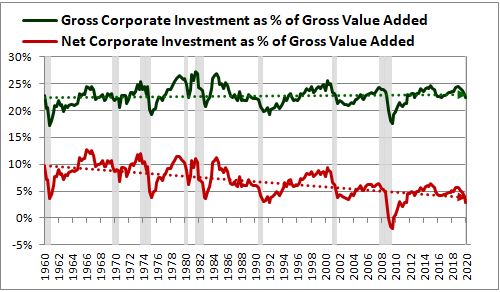

Another feature of the data worth noting is the steady decline in corporate investment that has occurred over time. At the 1979 cycle peak, corporate investment was 6.5% of GNP. Ten years later, at the 1989 cycle peak, it was only 3.8% of GNP.

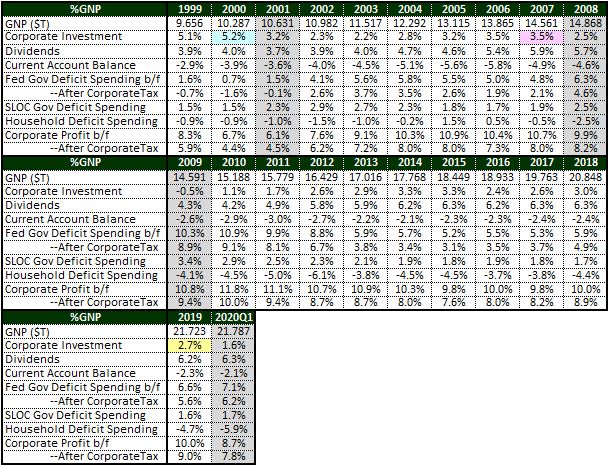

We see a continued decline in the data from 1999 through the present:

At the height of the 1999-2000 technology boom, corporate investment was 5.2% of GNP. At the height of the mid 2000's expansion, it was 3.5% of GNP. At the height of the most recent expansion, it was only 2.7% of GNP, close to a third of its value in 1979.

The declining trend in corporate investment is sometimes cited as evidence of poor corporate citizenship. In an effort to stimulate investment and job creation, legislators and policymakers have consistently given the corporate sector what it has asked for, reducing the tax, regulatory and financing burdens imposed on it. In response, it has shrunk its investment outlays and used the proceeds to pay dividends and buy back shares, expenditures that benefit shareholders and no one else.

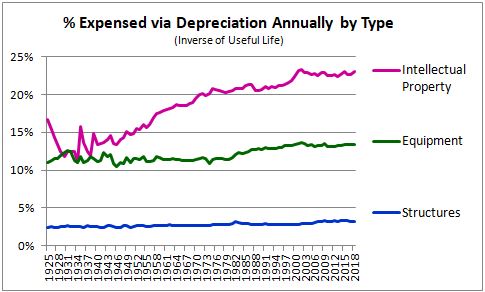

In defense of the corporate sector, we should note that a substantial portion of the decline, if not all of it, is the result of accounting conventions. Unlike GAAP, NIPA treats research and development expenses as investments, capitalizing them as intellectual property and depreciating them over an assigned useful life. The average useful life that it assigns to them (4-5 years) tends to be much shorter than the average useful lives that it assigns to traditional investments in equipment (7-8 years) and structures (25-30 years).

The chart below shows the average percentages of the net stock of different types of corporate fixed assets that were expensed via depreciation in NIPA each year from 1925 through 2018. As you can see, the percentage of intellectual property investments expensed via depreciation each year has grown over time, indicating a shrinking assigned useful life. The number is now between 20% and 25%, reflecting an assigned useful life of only four to five years (source: NIPA Fixed Asset Tables 4.1, 4.4):

In recent decades, as corporate investment has shifted towards intellectual property and away from equipment and structures, the result has been an effective increase in the depreciation expense assigned to the same level of gross investment, causing an apparent decline in investment net of depreciation. If the shortened useful life that NIPA assigns to intellectual property investments is accurate, then the associated decline in net investment is real and should be taken seriously. But if it isn't accurate, then the decline should be ignored.14 Either way, actual gross corporate investment as a percentage of gross corporate output (value added) has not actually declined (source: NIPA Table 5.1):

If we were to reconstruct the profit equation using numbers gross of depreciation rather than net of depreciation, we would find that gross profit margins have increased significantly relative to net profit margins. Data on gross profit margins are not available for national corporations, but they're available for domestic corporations (source: NIPA Table 1.14):

As you can see, gross profit margins, which are essentially cash flow margins, have grown dramatically relative to net profit margins. In light of this result, a critic of the corporate sector could reasonably pose the question: "Why haven't your investment outlays kept up with the enormous growth in your cash flows?" Presumably, the answer is that attractive investment opportunities have become less plentiful over time, leading corporations to instead direct their excess cash flows into dividends and share buybacks.

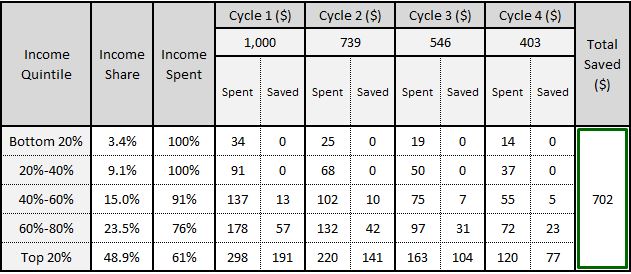

Forecasting Likely Profit Outcomes in the Current Environment

The deficit that the U.S. government is expected to accrue in response to the COVID-19 pandemic represents financial wealth that will be injected into the private sector. The impact that this wealth will have on corporate profits will depend on what happens to it when it gets injected. Someone in the private sector will have to withhold it—who will that be? How much spending will it trigger in the process of being withheld? The answers to these questions will depend on where the injection is delivered. A corporate tax cut, for example, is a direct injection into the corporate sector. It does not require any subsequent activity to count as profit. A household tax cut, however, will only affect profit if the proceeds get spent, directly or indirectly.

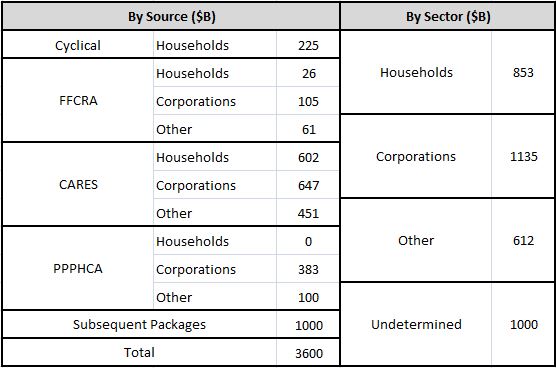

The Congressional Budget Office (CBO) estimates the current structural federal deficit to be roughly $1.1T. This deficit is the deficit that would have been incurred if the COVID-19 downturn had never happened. The additional deficit that will be incurred will originate from cyclical impacts associated with the downturn, e.g., declining tax revenues and increased transfer payments, and from the series of economic relief measures that have been implemented.15

The economic relief measures contain certain types of fiscal outlays that are clear injections into a specific sector: examples include expanded unemployment benefits and direct payments, which are direct injections into households, and tax cuts and forgiven loans, which are direct injections into corporations.16 The destinations of other types of outlays, such as funding for COVID-19 testing, are more difficult to pin down. In the table below, I've put together a very rough estimate of the likely destinations of the outlays associated with each measure:

The left side separates the projected deficit into its legislative sources, while the right side shows the deficit by the expected destination of the outlay: households, corporations, and "other", which refers to entities such as state and local governments and non-profit organizations. The "unknown" category refers to outlays associated with future expected measures that have not yet been defined in legislation. Note that government loans do not constitute fiscal outlays unless defaulted on or forgiven, so the table only includes the forgivable portion of paycheck protection program (PPP) loans. We assume that the Fed will break even on the sum total of its asset purchases and direct lending activities, and therefore we exclude the collateral that the Treasury has provided to the Fed from the tally.

As you can see in the table, a significant portion of the outlays are set to go directly into the corporate sector. Some of that revenue will go to costs and some will go to profit, offsetting organic profit losses incurred in the downturn. If the offset is sufficient to quench corporate withholding demand and stimulate investment and dividend spending, then the outlays will have the potential to multiply in additional profit, assuming that the recipients of the associated income spend it back. But if the outlays aren't sufficient to quench corporate withholding demand, then they will show up as corporate withholding and nothing else—profit that sits idle on corporate balance sheets.

Similarly, if the outlays to households and other non-corporate entities are sufficient to quench the withholding demand of those entities and stimulate spending on corporate goods and services, then they will translate into additional profit for the corporate sector. But if the outlays aren't sufficient to quench the withholding demand, then they will show up as withholding and nothing else—income that sits idle on non-corporate balance sheets.

Without question, the outlays are going to exert multiplier effects on corporate profit. The question that will determine the ultimate profit outcome is whether those effects will be sufficient to offset the negative multiplier effects associated with the downturn—corporate layoffs leading to household spending reductions leading to declining profits leading to further layoffs leading to further household spending reductions and so on in a vicious cycle. With respect to that question, the most important consideration is the epidemiological consideration.

At one extreme, we can envision an optimistic scenario in which the virus naturally goes away, or in which an effective vaccine or other conclusive medical solution is expeditiously developed. All of us—including those of us who are hypochondriacs—would then be able to return to our normal behaviors without fear of getting sick. The elevated withholding demand would gradually decline, prompting households to spend and businesses to hire and invest. These improvements would be occurring while the government injects record amounts of financial wealth into the system, wealth that someone has to withhold. Given the lack of an excess profits tax, corporate profit in such a scenario could very well end up being higher than it was before the pandemic, at least from the point of recovery forward.

At the other extreme, we can envision a pessimistic scenario in which the virus continues to aggressively circulate and infect, and in which a satisfactory vaccine or other medical solution proves to be elusive. Not everyone will maintain current behavioral changes under such an outcome, but enough people probably will, forcing the economy to undertake a more painful and drawn-out restructuring of the kinds of goods and services that it's aligned to produce. The current state of fragile employment, reduced confidence, weak investment, and tepid spending would then persist. Under such a scenario, current levels of deficit spending could prove entirely insufficient to quench the private sector's increased withholding demand, leading to a significant net decline in profits.

With respect to profits in a pessimistic scenario, some have expressed concern that the presence of the virus will increase corporate operating costs. But we have to remember that one entity's "cost" is another entity's income. If the virus forces corporations to spend more in their operations, the profit impact will be determined by what the recipients of that increased spending—presumably, households, but also other corporations—do with the income created by the spending. If they withhold it, either out of preference, or out of an aversion to price increases in the areas where they would otherwise spend it, then the effect on profit could be negative. But if the recipients spend it back into the corporate sector, the effect could be a wash.

In the chart and table below, I generate a tentative 2020 NIPA profit forecast by assigning specific numbers to the terms in the equation. I apply the pre-tax version of the equation using the following conservative assumptions:

A pre-corporate-tax federal government deficit of $4.84T (consisting of an after-corporate-tax deficit of $4.7T plus $140B in corporate taxes collected), 22.3% of GNP.

A current account balance and state and local government deficit of -2.1% and 1.7% of GNP, respectively, equal to the trailing twelve-month values as of the end of the first quarter of 2020.17

Dividends of 4.7% of GNP, calculated by assigning an estimated decline equal to the decline observed in the 2009 recession.

Corporate investment of -2.0% of GNP, equal to the level seen in 1943, the year of peak war-related retrenchment. Note that investment is a net term, so a negative number indicates gross investment insufficient to offset depreciation.

Household withholding of 16.0% (i.e., household borrowing of -16.0%), equal to roughly three-quarters of the after-tax government deficit, the same ratio seen in 1943.

The black line in the chart below shows the resulting profit forecast:

The table below shows the numbers in the equation. To obtain after-tax numbers, I simply apply the effective corporate tax rate for 2019 to the pre-tax estimates:

Under the stated assumptions, after-tax corporate profit drops from around 9% of GNP before the pandemic to around 7.7% of GNP after it (see 2020E1 in the table). That drop, when coupled to the CBO's estimated 2020 GNP drop of 5.6%, produces an overall profit drop of roughly 20%. Not a good outcome, but dramatically better than the Great Depression outcome that would have ensued in the absence of a strong fiscal response.

If we alter the forecast to reflect the corporate investment level observed in the 2009 recession, which is roughly the same as the level calculated using CBO's current projections, we get an after-tax profit of 9.0% of GNP (see 2020E2 in the table), the same number seen in 2019. The overall profit decline relative to 2019 ends up matching the GNP decline—a drop of only 5.6%. Such a small decline might seem unrealistic, but the enormous contribution that the government is making has left it well within the realm of possibilities.

It's important to note that these are estimates of NIPA profits, which only capture income from current production. Actual earnings numbers reported by companies in accordance with generally accepting accounting principles (GAAP) will likely contain larger downward swings, given the need to write down the values of past investments. Regardless, the important takeaway is that investors should not be surprised if corporate profits end up coming in stronger than expected for a recession as deep as this one has been—the government's actions have quite literally changed the equation.

For fundamental investors, the profit numbers that emerge for 2020 shouldn't be the focus. Equity value derives from a long-term stream of future cash flows, and 2020 is only a single year in that stream. When looking out over the long-term, the important point to remember is that the virus doesn't damage actual physical or intellectual capital—the assets that make corporations valuable. It simply prevents the public from making full use of those assets, despite otherwise wanting to. The lack of utilization is obviously a problem for corporations in that it deprives them of cash flow and exposes them to the risk of bankruptcy. But If the government, through its stimulus and liquidity provisions, can successfully bridge the system through the period of reduced utilization associated with the pandemic, then everything can eventually go back to the way it was, with the only cost being a temporary period of reduced income.

Instead of spending the wealth that the government injects through its deficits, cautious households may choose to withhold it, preventing it from turning into profit. But even if this happens, the benefit to profit will not be lost. The wealth, in being withheld, will lead to a strengthening of household balance sheets, which will free up space for households to increase their borrowing and spending in future years, causing an increase in profit that shows up with a lag. So even if the pandemic imposes a year or two of profit weakness on the corporate sector, that weakness can get recouped in the strength that follows, assuming that the actual problem—the virus—gets solved.

Profit Outcomes in an Upside-Down Market

The chart below shows year-over-year changes in the earned disposable income and consumption spending of U.S. households from January of 1960 through May of 2020.18 The upper lines (red, green—left axis) represent nominal changes and the lower lines represent real changes (blue, yellow—right axis) (source: NIPA Tables 2.4.5U and 2.6):

These aggregates grow together because they depend on each other: disposable incomes are the funding sources for consumption expenditures, and consumption expenditures are the revenue sources for disposable incomes. Periodically, their growth rates decline, sometimes to levels below zero.

What causes these declines?

One possible cause is policy. In order to grow, economies need certain monetary and fiscal conditions to be met—e.g., available credit at economically-viable rates, a government deficit sufficient to quench private sector withholding demand, and so on. When these conditions are challenged through policy actions, growth can fall or shift into contraction. Outside of policy, we can identify at least three additional causes of growth declines: Supply Shocks, Supply-Demand Mismatches, and Financial Wealth Contraction. We discuss each cause below:

(1) Supply Shocks: Events can occur that reduce the economy's capacity to produce goods and services that consumers want to consume. The production of those goods and services is the basis for income and spending, and therefore reductions in that capacity can lead to declines in both.

To illustrate with an extreme example, suppose that a gigantic meteor were to slam into some part of the country, destroying meaningful parts of the local economy. Everyone who earns income from those parts would lose income, and everyone who consumes goods and services produced in those parts would have fewer goods and services available to purchase and consume. If the shock proves to be inflationary, nominal levels of income and spending may remain constant. But real income and spending will necessarily fall.

(2) Supply-Demand Mismatches: Parts of the supply-side of the economy can become misaligned with the demand-side, structuring themselves to produce goods and services that are not sufficiently wanted. Alternatively, events can occur that cause the consumption preferences of the demand-side of the economy to change more rapidly than parts of the supply-side can keep up with. In both cases, income and spending growth will slow.

COVID-19 is an example of the latter case. Consumers like to eat at restaurants, go on vacations, attend live events, and so on, and the supply-side of the economy has correctly responded to those preferences by organizing itself to produce the desired supplies of those activities. Unfortunately, the ongoing presence of COVID-19 has dramatically reduced consumer demand to engage in the activities, with the result being a sharp drop in overall consumer spending. Incremental spending that would have gone into the activities has no reason to go elsewhere, so it has disappeared.

(3) Financial Wealth Contraction: The private sector has the ability to create financial wealth through credit expansion and through the pricing of assets. Sometimes, it uses these processes to create wealth that doesn't deserve to be created—wealth that isn't tied to the production of goods and services that people actually want. The destruction of this wealth, either naturally or in response to policy action, can force affected individuals to reduce their spending.

To illustrate with an extreme example, suppose that a very large segment of the population starts speculating in Bitcoin, using leverage where available. The price rises to $10,000,000, creating enormous financial wealth for millions of people. This wealth isn't real, it isn't tied to the production of goods and services that consumers actually want to spend money on, and therefore it won't be able to generate the cash flows necessary to justify its existence or service the debt on which it was built. If allowed to spill over into broader spending, it will put upward pressure on prices, driving a monetary policy response that will jeopardize the speculative fervor that is holding it together. Whether monetary policy ends up being the catalyst, or some other catalyst emerges, the system will find a way to destroy the wealth. When that happens, the unlucky people stuck holding it will be forced to reduce their spending—not because they don't want to spend, but because they can't afford to. They will have effectively given their wealth away to the people who they bought Bitcoins from.

The economic pain associated with these processes is not a mistake. It's a consequence of losses that need to be accepted and imbalances that need to be corrected. With respect to supply shocks, when the economy's productive capacity is damaged, reduced output is a given. Someone has to take the associated losses. With respect to supply-demand mismatches, if a part of the economy is producing things that people don't want, the financial squeeze that affected shareholders and employees will experience is by design—the system is asserting itself, forcing economic resources that are being inefficiently utilized to redeploy themselves in ways that meet the actual demands of the population. With respect to financial wealth contraction, if credit expansions and asset bubbles have been used to create financial wealth that is not backed by actual real wealth—the capacity to produce real things that are wanted by the economy—defaults and asset price declines are the proper remedy. The spurious wealth never should have been created and needs to be taken back.

The problem with the pain experienced in these processes is that it tends to propagate, moving well beyond its starting location. The justified losses experienced at ground zero will tend to depress income, spending and credit availability in other areas of the economy, causing losses that eventually spread everywhere through negative multiplication. As equity investors, we can use diversification to dilute away the risks associated with a single business or a single sector, but we can't use it to dilute away the risk of broader damage of this type—the risk is system-wide.

When consumption spending declines, legislators and policymakers have the ability to intervene, delivering liquidity and financial wealth to the places where it's needed. But intervening comes with costs, including: (1) unfairness and moral hazard, which can occur when people are protected from market consequences that they should have to face, (2) prevention of necessary adjustments, which can occur when the injected liquidity and financial wealth remove the stress that would otherwise force the adjustments, (3) inflation, which can occur when the liquidity and financial wealth that are injected as a remedy lead to more spending than the economy can support.

In a laissez-faire system, legislators and policymakers assign infinite weight to these costs and therefore never intervene. They leave the system alone and allow losses to negatively multiply until the damage has run its full course. If you are a diversified equity investor in a laissez-faire system, anything that causes a downturn in consumption spending will therefore represent an existential risk to you. If the downturn gives rise to a runaway contractionary process, the equity tranche of the economy will get wiped out and you will suffer extreme losses, regardless of whether you are diversified across your holdings.

The COVID-19 situation is unique in that none of the normal costs associated with intervention are present. With respect to unfairness and moral hazard, nobody did anything wrong, and therefore there's no need to worry about the implications of providing assistance. With respect to adjustment, if the problem of the virus can eventually be resolved, then there's no need for the supply-side of the economy to adjust—in fact, we don't want it to adjust, we want it to maintain the ability to produce the things that it was producing before the virus emerged, because consumers will go back to wanting those things when the virus goes away. With respect to inflation, current rates of inflation are very low and are likely to go even lower in the absence of aggressive policy action.

With these costs eliminated from the equation, it's no surprise that legislators and policymakers have responded to the pandemic by implementing the single largest stimulus intervention in history. If there were ever a worthy time to intervene, this is it.

To illustrate the effects of the COVID-19 intervention, the chart below shows U.S. household income alongside consumption spending for the months of January through June of 2020. The earned disposable income column represents all forms of household labor and capital income, to include income associated with government programs funded by the recipient. The government assistance column represents all forms of income not funded by the recipient, which includes income associated with normal and enhanced unemployment insurance, medicaid, and direct payments to households. The total disposable income line is the sum of the two columns (source: NIPA Tables 2.4.5U and 2.6):

From the January peak through the April trough, consumption spending fell precipitously, suffering a 19% contraction. This contraction coincided with a 7% contraction in earned disposable income. Total disposable income, however, grew by 14%, reflecting the enormous government assistance provided by the CARES act. The assistance was enough to turn the largest three-month income contraction in U.S. economic history into the largest three-month income expansion.

When this assistance expires, legislators will have to confront a critical set of questions. Should they renew it? If so, should the amount of assistance—in particular, the $600 per week currently being paid in enhanced unemployment benefits—remain the same? Should it be reduced? Should it be increased? These questions will be difficult for legislators to answer because the assistance was not provided as part of a well-defined, well-understood policy strategy. Legislators saw the economic pain that was being experienced and came up with an arbitrary fiscal number to inject in relief.

Before the pandemic, nominal household disposable income was growing somewhere between 4% and 5% per year. If the goal of the intervention is to avert the contraction associated with the pandemic, then a potential fiscal response that would make sense would be a response that targets that income growth rate. In deciding on assistance, legislators would examine the state of the private economy and calibrate the assistance to ensure that total household disposable income continued to grow at 4% to 5% per year.

On a year-over-year basis, earned household disposable incomes are still in contractionary territory relative to the peak. They have to be, given that significant parts of the economy remain impaired by the virus. Fiscal assistance therefore needs to be extended. The amount of assistance provided in the CARES act, however, has caused total household disposable income to significantly overshoot the normal rate, driving it up by 9% relative to the prior year. For income growth to return to the normal rate, a reduction in the amount of assistance may be needed.

We refer to a policy strategy that calibrates deficit spending to achieve a targeted income growth rate as fiscal income targeting. The strategy is not explicitly employed by any market-based economy at present, but it may be employed in the future as politicians become more comfortable with deficit spending. If you are a diversified equity investor, its implementation will significantly change the risk profile of your investments. The prospect of a broad decline in the incomes of the customers of your companies—a serious, unavoidable risk in the traditional laissez-faire framework—will disappear. Bad news won't be as bad, because it won't be able to propagate to aggregate household income. As long as the companies in your portfolio continue to produce goods and services that consumers are willing to spend money on, those companies will continue to receive the revenue that they need in order to remain profitable.

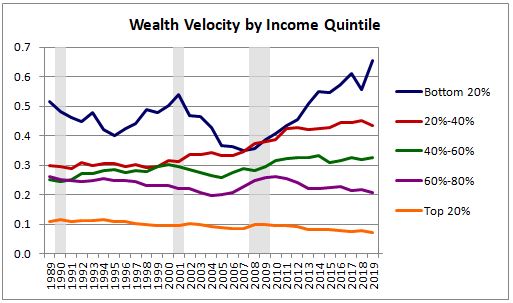

The problem with fiscal income targeting is that households aren't necessarily going to spend the income that they receive. Instead of spending it, they can choose to withhold it, which is what they've done in the current pandemic, evidenced by the 7% decline that has occurred in total consumption spending (despite a rise in total disposable income). As a diversified equity investor in a fiscal income targeting regime, you are fully exposed to the risk that households will withhold the assistance delivered to them. Bad news on the economy could therefore still be bad news for you if it causes that risk to materialize.